USFS Plant Database

Native American Ethnobotany, University of Michigan)

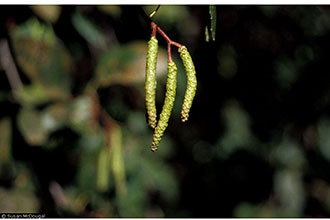

The scientific name of white alder is Alnus rhombifolia Nutt. (Betulaceae). White alder hybridizes with thinleaf alder in southwestern Idaho.

White alder grows along permanent streams and adjacent slopes. On 4 sites across western Oregon, its presence was positively correlated with streamside, and on the Lassen National Forest, California, white alder was negatively correlated with distance from streams. It is mostly restricted to flood zones and becomes infrequent farther upland. The most well-developed white alder forests are along rapid, well-aerated perennial streams with high spring runoffs. In dry years, white alder is a better indicator of moist soils than either cottonwoods or willows. White alder is most common along rivers and third-order streams. In the Siskiyou Mountains of California and Oregon, it was most frequent (90%) on the most mesic sites by large streams. It grows along small streams in the Coast Ranges and the Sierra Nevada, however. For example, white alder is most common on upper stream reaches in the Central Coast Ranges above Carmel Valley. (Plant Database)

White alder has numerous ethnobotanic applications. Traditionally, Native Americans formulated many medicines using different parts of the tree. Decoctions (boiled extractions) made with dried bark were used as treatments for diarrhea, dermatological issues, consumption, blood purifiers, and facilitation of childbirth. Dried wood was also used to make poultices for burns.

The bark can also be used to make a reddish dye, customarily used to paint fishermen’s bodies and as a dye for basketsand deerskins. When burned, the bark smoke could tan white buckskin yellow. White alder roots were harvested to make baskets, and young shoots served as material to make arrows. (Native American Ethnobotany)